A treasured tradition served with a side of polka

By: Nora Dummer

When I lived in Seattle, my Minnesotan heritage was my party trick. My friends squealed at every utterance of bag, pontoon, and a well-placed dontcha know; as a bartender, I leaned into the accent anytime I had to kick someone out, hoping it would soften the blow. I learned quickly that Midwestern culture is somewhat exotic to the coasts and that what I once regarded as normal as Sunday football was now an anomaly for amusement.

There was no better place to illustrate this distinction than the dinner table. My potluck contributions were a delightful mélange of delicacies: sherbet Jell-os, cornflake-laden hot dishes, dairy-product potpourris. The fare that best perplexed my friends, however, wasn’t because of the dish itself, but rather because of the lore behind it – the Rybak family booya.

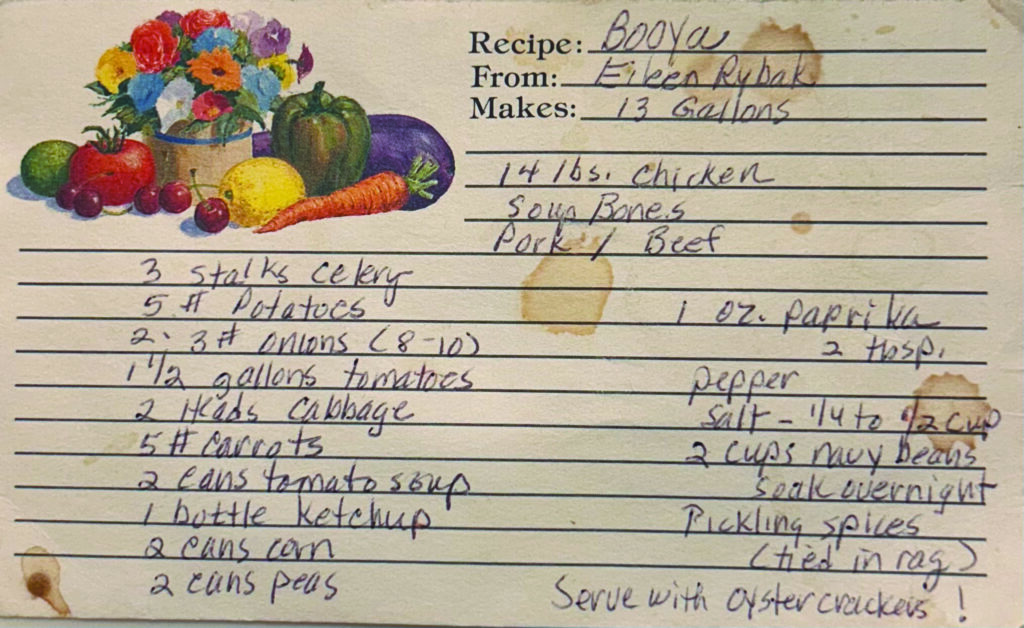

Most Upper Midwesterners have at least heard of a booya while the rest of the country only knows the word as analogous to an expression of excitement. The truth is, even if you’re familiar with the concept, the exact definition and flavor differs according to state, city, family and God. As far as I can tell, there are just three things agreed upon when it comes to booya: 1) that the word is both noun and verb, 2) oyster crackers are a must, and 3) your family’s recipe is the best and only recipe that matters. The constitution, origins and even spelling are all hotly debated.

A booya is “neither soup, nor stew, but something of both”, usually containing a combination of pork, beef and chicken but adding rabbit, veal, venison, turkey, turtle, squirrel or bear wouldn’t be out of the question. The vegetables range from root – rutabagas, potato, kohlrabi, carrot – to standards like cabbage, peas, green beans and alliums. It’s typically cooked for several hours in a massive cast iron kettle over a flame; 7 gallons is modest, 50 is typical, 500 isn’t abnormal. Most people accept that its origins lie in Belgium, but I’ve also heard arguments for Germany, Hungary and France (at least for the word itself, a bastardization of bouillon).

The majority of Minnesotan booyas are held in St. Paul, likely a holdover from the influx of eastern Europeans who immigrated there to work in the stockyards in the early 20th century. In fact, the city proclaims itself to be the “Booya Capitol of the World”, though Green Bay would likely contest this idea. (Wisconsin booyah relies more on chicken, less on tomatoes, and is generally spiced solely with bay.) Today, you can find booyas across the upper Midwest as fundraisers for churches, community centers, lodges and fire halls or hosted by brave families willing to feed a crowd. While some start as early as June, most consider it a fall event when the air is crisp and a hot soup is welcomed.

The Rybak family, of course, has their own opinions on the best way to booya. For one, using boneless skinless chicken is sacrilege; oxtails are encouraged. Using bones and skin results in a soup that is full of both body and flavor, absolutely worth the impossible task of having to wade through the murk to later discard them. A baseball sized cheesecloth bag is stuffed with pickling spice to impart a warm depth to the soup. Not one, not two, but three types of tomato products fill the pot (canned tomatoes, tomato soup and ketchup), likely a nod to a mid-century genesis when Campbells and Heinz ruled the recipe cards. Green beans have absolutely no place in it. The only appropriate stirring utensil is a giant canoe paddle. The best heat source is the adjustable flame from a propane tank hidden in the bottom of the garbage can that houses the kettle; wood is too hot and unpredictable.

Naturally, all of these rules were put in place by my grandfather. Edward Rybak was feverously passionate about his booya, so much so that my grandmother would bristle at the mere mention of the word, anticipating the labor and logistics to come. Eddie had a penchant for parties – a trait he inherited as a second-generation Pole and the youngest of nine children. His family enjoyed each other’s company as much as they enjoyed their food and drink. (They were the kind of family who would throw a poprawiny – a second party the day after a wedding – just to prolong the celebration.) He owned and operated Eddies Corner Bar in New Brighton for 30 years before working for the Tex-Gas company (hence the propane), and likely began hosting his own booyas to fill the void after the bar closed down. That, and his unwavering love for soup.

Eddie was first introduced to booya from St. John the Baptist, his local church which has used it as a fundraising event since 1931. He and his wife Eileen were regulars with their family, always contributing two pounds of veal to the pot back when the community supplied ingredients. In 1978 the event expanded to occupy a whole weekend; polka mass, cake walks, bingo and fish ponds were just some of the activities that delighted their four daughters. (Today, the tradition continues; each year the church sells enough booya to fill nine 60-gallon kettles.)

My grandpa brought the booya to his own backyard in the 1970’s at his cabin on Little Rock Lake, a miraculous feat making 14 gallons of soup out of a double-wide. Over the next forty years it bounced around between relatives’ houses, Eddie maintaining his position as head booya chef for as many as he could muster.

Though the location changed, the ritual remained the same. With most ingredients already prepped by Eileen, Eddie would wake up before the sun to get the meat in the pot by 6:30 am, typically outside in the crisp October air but if the weather threatened, in an open garage. Clad in his signature trucker cap, sports jacket and apron, he added the whole chicken parts and soup or neck bones first, covering it all with water to boil and then simmering it gently for a half hour or so until adding the cubed pork and beef. Over the next six hours he stirred in the soaked navy beans, the hearty vegetables, the tomato, and the soft vegetables to finish. About half way through, he would add the pickling spice and continually sip the soup as the cheesecloth bobbed like a buoy, removing it when it achieved that signature Rybak flavor. Like a captain at the helm, with the oar in his hand he wouldn’t stray from his post lest the booya stick and burn, “ruining the whole damn thing”. As family and friends arrived, he’d crack jokes and beers in tandem, threatening to throw roadkill into his pot and speaking in broken Polish with that dimpled grin on his face as if he had any idea what he was saying.

While Eddie’s legacy was the party, Eileen’s was music. Aspiring to hit the stage of Lawrence Welk, she taught her daughters to sing in four-part harmonies at an early age, rounding out the girls with her grounding alto. In the early booya days, she would bust out her accordion for renditions of the Chicken Dance or Roll Out the Barrel, eventually passing it off to her eldest daughter Linda and then finally, to a local booya-loving musician by the name of Dick Szyplinski who would serenade the dancing crowd with hours of polka. The Rybak sisters would often make a cameo appearance with their trademarked harmonies before rejoining their mom for a dance.

As the music played on, no one went hungry waiting for booya (this was a Rybak gathering, after all). Folding tables with mountains of salty snacks and dessert bars – and quintessential apple squares – were where most of the kids and eager adults flitted about. The day progressed with guests enjoying a styrofoam bowl of booya heaped with oyster crackers, then a beer or two, then maybe another bowl and three or four desserts to conclude the meal. Each walked away with a full belly, a plate of desserts, and an old recyclable of the rich stew. The party ended with the sun.

This tradition was so woven into the fabric of my family culture, exact details are elusive and many are lost to time and memory. (I couldn’t interview Eddie and Eileen – my grandfather passed in 2018 and my grandmother passed, coincidentally, mere hours after getting the green light to write this story.) No one remembers exactly what year it started or ended; it simply was until it wasn’t.

When I decided to throw a housewarming party last fall, I knew there was only one answer to the question of what to serve. After nearly 20 years of living in the Pacific Northwest, it was time to christen my new home the only way I knew how. I didn’t have a kettle but I did have my two biggest pots simmering seven gallons on my stovetop. I didn’t have an accordion player but I did have the jovial crooning of Harry Belafonte over the stereo. The familiar spice wafted through the air, the scent of both labor and love, as my rellies chatted over the snack table and the Vikes played on the projector. It wasn’t Eddie’s party, but it was mine and it was perfect.

Traditions tie us to our community, our family, our ancestors; they connect us with the seasons and anchor us to time. They are so much more than a party trick. When I made booya, it brought me back to my childhood while paradoxically demanding that I stay fully in the present, diligently stirring the pot lest I burn it and ruin the whole damn thing.

Nora Dummer is a chef and cooking class instructor who’s recently returned to Minnesota after a long, soggy stint in Seattle. In the rare moments of relief from chasing around her two young children, she is busy building her all-things-food-business, for the love of cuts and burns.